Translate this page into:

A descriptive study of patterns of genital dermatoses in patients in south India and evaluation of their quality-of-life

*Corresponding author: Anupa Mary Job, Department of Dermatology, Venerology and Leprosy, Government Medical college, Palakkad 678 013, Kerala, India. anupamaryjob@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Job AM, Bindurani S, Mohan M, Mohanasundaram SN. A descriptive study of patterns of genital dermatoses in patients in south India and evaluation of their quality-of-life. J Skin Sex Transm Dis. doi: 10.25259/JSSTD_75_2024

Abstract

Objectives

The objective of this study was to describe various venereal dermatoses (VD) and non-venereal dermatoses (NVD) of external genitalia and evaluate the quality of life (QOL) in patients with various genital dermatoses.

Materials and Methods

In this cross-sectional study, patients with genital dermatoses attending a tertiary care center in South India over a period of 2 years were evaluated. Demographics and clinical features were recorded. QOL was assessed using the dermatology life quality index (DLQI) questionnaire.

Results

Among the 100 patients with genital dermatoses, 63% of patients had NVD, and 37% had VD. The mean DLQI score in the study was 5.8 ± 4.437. About 33% of patients had a small effect on QOL due to genital dermatoses. Furthermore, 61.9% and 59.4% of patients with non-venereal and VD, respectively, had small and moderate effects on QOL due to their disease. The DLQI scores showed a tendency to worsen with advancing education status and also in patients with coexisting skin lesions.

Limitations

Patients below 18 years of age with genital dermatoses were excluded from the study. Further, as this study was conducted during the COVID outbreak, the sample size was small, which may have led to the exclusion of rarer dermatoses affecting the external genitalia.

Conclusion

Overall, patients had a small effect on QOL due to genital dermatoses. Worsening in QOL was associated with advancing education status and with the presence of co-existing skin diseases. There is a dearth of studies assessing QOL in patients with genital dermatoses in South India. Such studies addressing the psychosocial morbidity associated with these disorders may be pertinent in designing a holistic management plan while treating these disorders.

Keywords

Genital dermatoses

Non-venereal dermatoses

Quality of life

Venereal dermatoses

INTRODUCTION

Skin in the genital area is an extension of the skin elsewhere in the body and can be affected by common skin disorders that may incidentally affect the genital area or with disorders predominantly confined to this area, including sexually transmitted diseases (STIs). Disorders affecting the external genitalia can be broadly classified as venereal and non-venereal dermatoses (NVD). Genital dermatoses are common; however, due to the stigma associated with these disorders, many patients do not seek medical attention and prefer self-treatment. They are known to cause a significant reduction in the quality of life (QOL). An online survey by the British Association of Dermatologists noted that patients with vulvar dermatoses were twice as likely to have suffered from depression, with 22% reportedly having contemplated self-harm or suicide due to the same.[1] Interestingly in men, such statistics are not available in the literature for review. Most studies assessing QOL in patients with genital disorders currently available in the literature focus mainly on NVD. The purpose of this study was to describe various venereal and non-venereal genital dermatoses and to evaluate the QOL in patients with these dermatoses.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

This cross-sectional study was conducted in the Department of Dermatology, Venereology, and Leprosy of our tertiary care institution in South India after obtaining permission from the Institutional Ethics Committee for a period of 2 years. The participants included 100 consecutive patients aged more than 18 years who were clinically confirmed to have genital dermatoses. Pregnant women and those with pre-existing severe and chronic psychiatric disorders (schizophrenia, bipolar affective disorder, dementia, and obsessive-compulsive disorder) were excluded from the study. After the informed consent process, a detailed history including demographics, symptoms, duration of illness, use of topical agents, and sexual practices were recorded on a preformed pro forma. A clinical examination was done, and if warranted, tests such as skin biopsy for histopathology study, Gram stain, potassium hydroxide stain, and/or Tzanck smear were done to arrive at a diagnosis.

Following this, the patients were instructed to fill out the dermatology life quality index (DLQI) questionnaire (which is a dermatology-specific QOL questionnaire designed by Finlay and Khan) on the basis of which their QOL was assessed.[2] The DLQI consists of ten specific questions about the impact of dermatological disease on QOL which covers six domains such as symptoms and feelings, daily activities, leisure, work and school, personal relationships, and treatment. Each question has four response alternatives, corresponding to scores from 0 to 3. The maximum score was 30. The higher the score, the more the impairment in QOL. The scores were assessed in the following way:

0-1 no effect on the patient’s life

2-5 small effects on the patient’s life

6-10 moderate effects on the patient’s life

11-20 large effects on the patient’s life

21-30 extremely large effects on the patient’s life.

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 22 for descriptive statistics. Inferential statistics were done using the Mann-Whitney U-test and the Kruskal-Wallis H-test. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Among the 100 patients included in the study, 58% were male, and 42% were female. The demographic details are listed in Table 1. The age group of the patients ranged from 18 years to 75 years, with a mean of 40.52 years. In the study group, 72% of patients belonged to the lower middle and upper lower strata with respect to socioeconomic status, as assessed by the modified Kuppuswamy scale for the urban population of the country. Further, 68% of patients had basic and less than basic education status. With respect to marital status, 68% of patients were married. In the study group, 78% of patients had no history to suggest high-risk sexual behavior.

| Characteristics | Frequency (n=100) (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Males | 58 (58) |

| Females | 42 (42) |

| Age | |

| <20 years | 5 (5) |

| 21-40 years | 49 (49) |

| 41-60 years | 32 (32) |

| >60 years | 14 (14) |

| Socioeconomic status | |

| Upper and upper-middle class | 28 (28) |

| Lower-middle and upper-lower class | 72 (72) |

| Education status | |

| Less than basic | 29 (29) |

| Basic (primary school) | 39 (39) |

| Intermediate (middle-high school) | 10 (10) |

| Advanced (university) | 22 (22 |

| Employment status | |

| Employed | 65 (65) |

| Unemployed | 35 (35) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 68 (68) |

| Unmarried/divorced or widowed | 32 (32) |

| High-risk sexual behavior | |

| Present | 22 (22) |

| Absent | 78 (78) |

| Duration of illness | |

| <1 month | 57 (57) |

| >1 month | 43 (43) |

| Presence of co-existing skin condition | |

| Yes | 33 (33) |

| No | 77 (77) |

| Symptoms | |

| None | 24 (24) |

| Itch | 41 (41) |

| Pain±burning sensation | 66 (66) |

| Discharge | 11 (11) |

| Ulcer | 8 (8) |

| Pattern of genital dermatoses | |

| Venereal dermatoses | 39 (39) |

| Non-venereal dermatoses | 61 (61) |

As for the clinical profile, 33% of patients in the study group had coexisting skin conditions. These included (a) autoimmune and inflammatory dermatoses such as vitiligo, urticaria, lichen planus, and seborrhoeic dermatitis, (b) bullous dermatoses such as pemphigus vulgaris, (c) infections such as tinea corporis, and (d) benign conditions such as acanthosis nigricans and acrochordons. It was observed that 76% of patients in the study group were symptomatic. Interestingly, 24% of females and 17% of males complained of multiple symptoms. Pain and burning sensation were the most common symptoms in the study group, and it was seen in 35% of females and 31% of males. This was followed by an “itch” which was noted in 19% and 22% of females and males, respectively. In the study group, 57% of patients had genital lesions of < 1-month duration.

Among the 100 patients examined, 63% patients were found to have NVD, and 37% had VD (Those patients with conditions such as genital candidiasis, which may have various modes of transmission, those with high-risk behavior, complicated candidiasis or partners with genital candidiasis were presumed to have candidiasis acquired by sexual mode of transmission and hence categorized under VD).

The NVDs observed in this study were grouped based on their etiopathogenesis as per Fitzpatrick and Gentry classification and are described in Table 2. The most common NVDs were inflammatory dermatoses (44.4%), followed by infestations and infections (28.5%).

| Non-venereal dermatoses (%) | Diagnosis and frequency (n=63) (%) |

|---|---|

| Congenital and benign disorders (n=11, 17.46) | Pearly penile papules (4, 6.34) Vestibular papillomatosis (1, 1.58) Sebaceous cyst scrotum (1, 1.58) Vulval skin tag (2, 3.17) Scrotal steatocystoma (3, 4.76) |

| Infections and infestations (n=18, 28.57) |

Furuncle (1, 1.58) Dermatophytosis (4, 6.34) Folliculitis (5, 7.93) Genital candidiasis (6, 9.52) Erysipela vulva (1, 1.58) Scabies (1, 1.58) |

| Inflammatory disorders (n=28, 44.44) | Lichen planus (4, 6.34) Scrotal dermatitis (11, 17.46) Zoons balanitis (2, 3.17) Irritant contact dermatitis (10, 15.87) Insect bite reaction (1, 1.58) |

| Malignant and premalignant (n=1, 1.58) | Pseudoepitheliomatous keratotic and micaceous balanitis (1, 1.58) |

| Pigmentary disorders (n=2, 3.17) | Vitiligo (2, 3.17) |

| Miscellaneous (n=3, 4.76) |

Genital pemphigus (1, 1.58) Fixed drug eruption (2, 3.17) |

Among the 37 patients with VD, 21.62% had genital warts and herpes genitalis. The various VD observed in this study are tabulated in Table 3. All six patients with genital molluscum contagiosum (MC) had spouses having similar genital lesions. Secondary bacterial infection of MC was observed in two females. All the five patients with syphilis were male. One had a primary chancre, while another was a serologically confirmed case of syphilis with a cigar paper scar suggestive of a healed primary chancre. The other three cases included annular and lichenoid syphilitic lesions on the scrotum.

| Venereal dermatoses | Frequency (n=37) (%) |

|---|---|

| Genital warts | 8 (21.62) |

| Genital herpes | 8 (21.62) |

| Molluscum contagiosum | 6 (16.21) |

| Syphilis | 5 (13.51) |

| Chancroid | 1 (2.70) |

| Pediculosis pubis | 2 (5.40) |

| Genital scabies | 2 (5.40) |

| Candidial balanoposthitis and complicated vulvovaginal candidiasis | 5 (13.51) |

The various venereal and NVD seen in this study in males and females are represented in Figures 1 and 2.

- Genital dermatoses in males; (a): Steatocystoma; (b): Scrotal calcinosis with tinea cruris; (c): Lichen planus; (d): Scrotal dermatitis with herpes genitalis; (e): Fixed drug eruption; (f): Pseudo-epitheliomatous keratotic and micaceous balanitis; (g): Genital scabies with inguinal bubo; (h): Molluscum contagiosum; (i): Genital warts; and (j): Annular syphilis.

- Genital dermatoses in females; (a): Ulcerative lichen planus; (b): Erysipelas; (c): Skin tag; (d): Vulvovaginal candidiasis; (e): Vitiligo; (f): Chancroid; (g): Molluscum contagiosum; (h): Genital wart; and (i): Herpes genitalis.

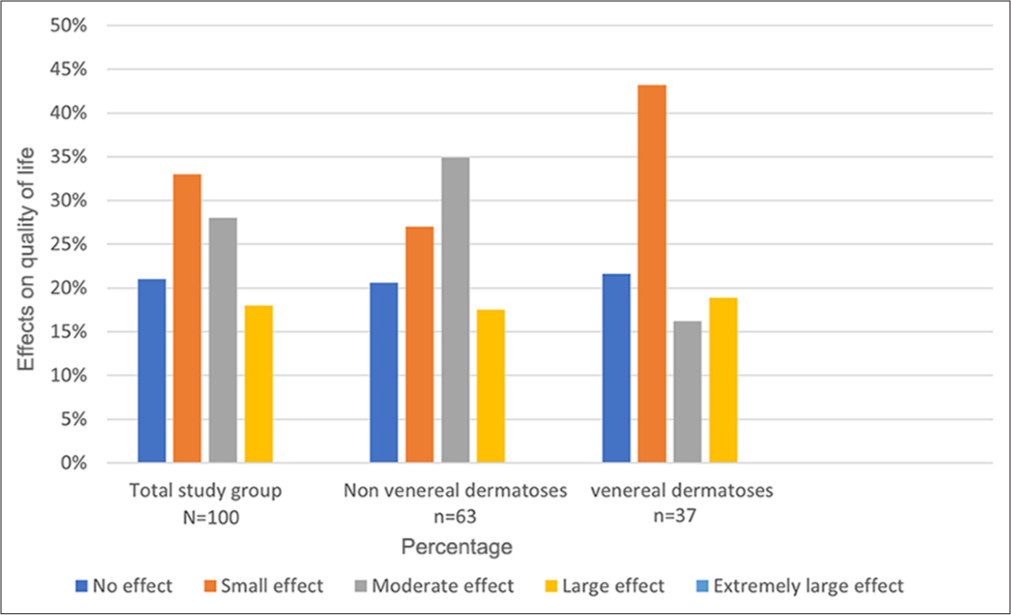

The mean DLQI score in the study was 5.8 ± 4.437. The DLQI score in the overall study group, along with separate representations in patients with non-venereal and VD, is illustrated in Figure 3. Among the 100 patients in the study group, 33% of patients had small and 28% had moderate effects on the QOL. Only 18% of patients had a large effect, and none had an extremely large effect on their QOL with respect to their genital dermatoses. It was observed that 61.9% and 59.4% of patients with non-venereal and VD, respectively, had small and moderate effects in QOL due to their disease. It was interesting to observe that 34% of patients with NVD had a moderate effect on their QOL, whereas 43% of patients with VD had a mild effect on their QOL. Nonvenereal genital dermatoses with a history of high-risk sexual exposure did not affect the QOL.

- The impact of genital dermatoses on quality of life based on dermatology life quality index score in entire study group, nonvenereal dermatoses, and venereal dermatoses.

We further compared the DLQI scores with various demographic and clinical variables, as described in Table 4. Patients with genital dermatoses showed worsening in QOL with advancing education status and with the presence of co-existing skin diseases. Although the DLQI scores were higher in NVD (mean DLQI score 6.16 ± 4.84) as compared to VD (mean DLQI score 5.41 ± 4.84), the difference was not statistically significant.

| Variables | Description | Mean DLQI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 5.79±475 | 0.992 |

| Females | 6±5.01 | ||

| Age | <40 years | 5.44±4.83 | 0.272 |

| 40 years | 5.82±4.64 | ||

| Education status | Less than basic | 4±371 | 0.031 |

| Basic | 6±5.06 | ||

| Intermediate | 9.3±0.3 | ||

| Advanced | 6.59±3.78 | ||

| Marital status | Married | 5.89±4.93 | 0.925 |

| Unmarried | 5.86±4.77 | ||

| Coexisting skin conditions | Yes | 7.30±5.67 | 0.019 |

| No | 5.18±4.24 | ||

| Non-venereal dermatoses | 6.16±4.84 | 0.133 | |

| Congenital+ benign+ pigmentary+ miscellaneous dermatoses | 4.35±3.76 | ||

| Inflammatory dermatoses | 8.32±5.78 | ||

| Infections+infestations | 5.07±3.85 | ||

| Venereal dermatoses | 5.41±4.84 | ||

| Viral etiology | 5.81±5.39 | ||

| Bacterial+ treponemal+ parasitic etiology | 5.90±4.50 | ||

DLQI: Dermatology life quality index. The values in bold highlight statistical significance.

DISCUSSION

Genital dermatoses may result from various etiologies, including STIs, non-sexually transmitted agents, inflammatory disorders, multi-system diseases, benign and malignant neoplasia, and external factors such as contact dermatitis and fixed drug eruption.[3] They are broadly classified as venereal and NVD. Most are multifactorial and are modified by anatomical, hormonal, biological, and frictional influences, posing a diagnostic challenge to clinicians. Further, various studies postulate that the onset of genital dermatoses, which usually coincide with suspected sexual contact, dramatically increases the levels of depression, anxiety, and stress in those patients affected. This also has an adverse effect on their QOL, more so in those with symptoms such as pain, itching, discharge, and swelling.[4,5] The purpose of this study was to describe the various venereal and nonvenereal genital dermatoses seen in patients attending the outpatient department of our institution and to assess their QOL using the DLQI questionnaire.

Demographic profile

In our study, the percentage of females who presented with genital dermatoses was lower when compared to males. This finding was similar to the observation by Vellaisamy et al., who, in their study, noted a male preponderance, with a male: female ratio of 1: 0.22. This could be attributed to social stigma, cultural taboos, and lack of knowledge associated with genital dermatoses in our subcontinent.[6]

Most patients in the study were in the age group between 21 and 40 years, which must be of concern as this comprises a majority of the reproductive age group. Our observation was comparable with a recent study by Geetha, where the participants fell in the age group of 20 and 45 years.[7]

Most of the patients in our study group were married. This was comparable with the study by Vellaisamy et al.;[6] however, our findings were not in accordance with the findings of Hogade and Mishra, who, in their study, found that NVDs were more common among unmarried males when compared to married males.[8]

Most of our patients had basic and less than basic education. Only a few studies on genital dermatoses assessed the education status of their study participants. Temel et al., in their study on genital dermatoses, found that the majority of their participants had advanced education status.[5] However, this could probably be explained by the fact that their study was conducted in an upper-middle income country and ours in a country with a developing mixed economy.

Clinical profile

The number of patients with NVDs was greater than those with NVD. This was similar to the findings by Temel et al., who, in their study, had 51.5% and 48.5% patients with nonvenereal and VD, respectively.[5]

The various NVDs observed in our study in decreasing order of frequencies are inflammatory disorders, infections and infestations, congenital and benign disorders, pigmentary disorders, miscellaneous (genital pemphigus and fixed drug eruption), and premalignant disorders. This was in concordance with the findings in a study on non-venereal genital dermatoses by Puri and Puri, in which inflammatory disorders were the most common dermatoses observed.[9] Among patients in the VD group, 59.45% had STIs with a viral etiology. This was in accordance with findings by Zahir et al., who, in their recent study of seventy patients with VD, found that 57.1% of patients had sexually transmitted infections with a viral etiology such as genital warts, herpes genitalis, and MC.[10]

DLQI scores according to groups and comparisons with demographic and clinical parameters

The mean DLQI score in the study was 5.8 ± 4.437, and 33% of patients had a small effect in QOL due to genital dermatoses. The observation that 61.9% and 59.4% of patients with non-venereal and VD, respectively, had small to moderate effects on QOL due to their disease was not in accordance with most studies assessing QOL in patients with genital dermatoses. For example, Mathon and Simran, and Sujana et al., found moderate impairment in QOL in their study on patients with non-venereal genital dermatoses.[11,12] In contrast, a recent study on the impact of genital pruritus on the QOL of patients observed that 66.8% of the patients had only a small effect, and no patients had extremely large impact on their QOL. Although this study by Renjana et al., used the pruritus intensity score and not the DLQI score, the fundamental objectives of our study were compatible with theirs, and comparison may seem plausible.[13]

We compared DLQI scores with various demographic parameters such as age, sex, marital status, education status, employment, and high-risk behavior status. The DLQI scores showed a tendency to worsen with advancing education status. In a study on anogenital warts in Syrian patients, Haddad et al., found worsening in QOL with advancing education levels. They postulated that those with advanced education status were probably more concerned after their diagnosis in addition to caring for their health by reading and inquiring about this disease and its link to potential complications.[14]

On comparing with various clinical parameters such as duration of illness, symptoms, coexisting skin lesions, and type of dermatoses, we found that DLQI scores were higher in patients with coexisting skin lesions, either related to (for example, genital pemphigus in those with cutaneous and other mucosal lesions of pemphigus) or unrelated to (for example, skin tags, acanthosis nigricans) their genital dermatoses.

With our finding of genital dermatoses having a small effect on overall QOL based on the DLQI questionnaire tool, the authors recommend a need for future research to formulate genital dermatoses-specific questionnaires with emphasis on symptoms, feelings and emotions, activities of daily living, relationships, sexual function, health concerns, and treatment. Having such a tool would enhance the clinical consultation and facilitate discussion, which is disease and person-specific.[15]

Limitations

Patients below 18 years of age with genital dermatoses were excluded from the study. Further, as this study was conducted during the COVID outbreak, the sample size was small, which may have led to the exclusion of rarer dermatoses affecting the external genitalia.

CONCLUSION

Genital dermatoses are more commonly reported in males and in the age group between 21 and 40 years. Overall, patients had only mild impairment of QOL due to genital dermatoses. Patients with genital dermatoses showed worsening in QOL with advancing education status and with the presence of co-existing skin diseases. There may be a need for quality research in the future to formulate genital dermatoses-orientated quality-of-life/outcome instruments for assessing patients with such disorders.

Ethical approval

The research/study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the Institute of Integrated Medical Sciences (Government Medical College Palakkad), number IEC/GMC/PKD/24/20/78, dated December 21, 2020.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- The impact of vulval disease on patients’ quality of life. J Community Nurs. 2016;30:40-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Dermatology life quality index (DLQI)--a simple practical measure for routine clinical use. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1994;19:210-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of life quality, anxiety, and depression in patients with skin diseases. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e22983.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of dermatology life quality index, depression-anxiety-stress scores of patients with genital dermatoses. Indian J Dermatol. 2023;68:399-404.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A study of pattern and assessment of life quality index in patients of nonvenereal dermatoses of external genitalia at a tertiary care center. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2023;44:49-55.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Impact of non-venereal genital dermatoses among female patients on the quality of life in a tertiary care center. Age. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2023;9:131-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A study of pattern of nonvenereal genital dermatoses of male attending skin OPD of tertiary centre in Kalaburagi. Int J Res Dermatol. 2017;3:407-10.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A study on non venereal genital dermatoses in North India. Our Dermatol Online. 2012;3:304-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Clinical pattern of non-venereal and venereal genital dermatosis in males attending dermatology OPD in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Pharm Clin Res. 2024;16:715-20.

- [Google Scholar]

- Non venereal genital dermatoses and their impact on quality of life. Int J Sci Res. 2022;7:820-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A clinical study of venereal and non venereal genital dermatoses in women. Eur J Mol Clin Med. 2022;4:2663-76.

- [Google Scholar]

- Study of genital pruritus in female patients attending the dermatology OPD at a tertiary care center in South Rajasthan. Int J Res Med Sci. 2024;12:1118-25.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- The psychosocial burden of anogenital warts on Syrian patients: Study of quality of life. Heliyon. 2022;8:e09816.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vulval skin conditions: Disease activity and quality of life. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2013;17:117-24.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]