Translate this page into:

Atypical presentation of Basidiobolus as cutaneous ulceration

*Corresponding author: K. Shreya, Department of Dermatology and Venereology, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India. shreyakgowda@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Baheti K, Shreya K, Singh P, Gupta S, Asati DP. Atypical presentation of Basidiobolus as cutaneous ulceration. J Skin Sex Transm Dis 2024;6:96-8. doi: 10.25259/JSSTD_43_2023

Dear Editor,

Basidiobolomycosis is a localized subcutaneous tropical mycosis characterized by chronic woody swelling of subcutaneous tissue caused by the fungi Basidiobolus ranarum.

A 55-year-old woman, a farmer by occupation with no known comorbidities, presented with multiple subcutaneous nodules on the back of her trunk for the past two years, which progressed to form diffuse infiltrated plaques, ulcers and sinuses discharging pus. The patient denied any history of trauma or surgery at the site. Examination showed an indurated plaque of size 30 × 20 cm, along with satellite nodules on the upper back. The finger was easily inserted below the edge [Figure 1]. On the surface of the plaque, there were two irregularly shaped necrotic ulcers of size 10 × 4 cm and 5 × 3 cm with undermined edges and necrotic slough. Multiple linear puckered scars with overlying skin atrophy and areas of hypo- to hyper-pigmentation were also seen over the plaque.

- Large indurated plaque of size 30 × 20 cm was present over the back extending from the nape of the neck to tenth thorasic vertibra level vertically, and bilateral mid-axillary line horizontally, satellite nodules present in the periphery of the plaque with discharging sinuses.

Based on history and examination, differential diagnoses of subcutaneous fungal infection, atypical mycobacterial infection, ecthyma gangrenosum, and pyoderma gangrenosum were considered. A complete hemogram showed microcytic hypochromic anemia and raised thyroid stimulating hormone. Blood sugar, liver and renal function tests, were normal. Free T3 and T4 were within normal limits. Serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV I and II) and hepatitis B and C infections were negative. Chest X-ray was normal.

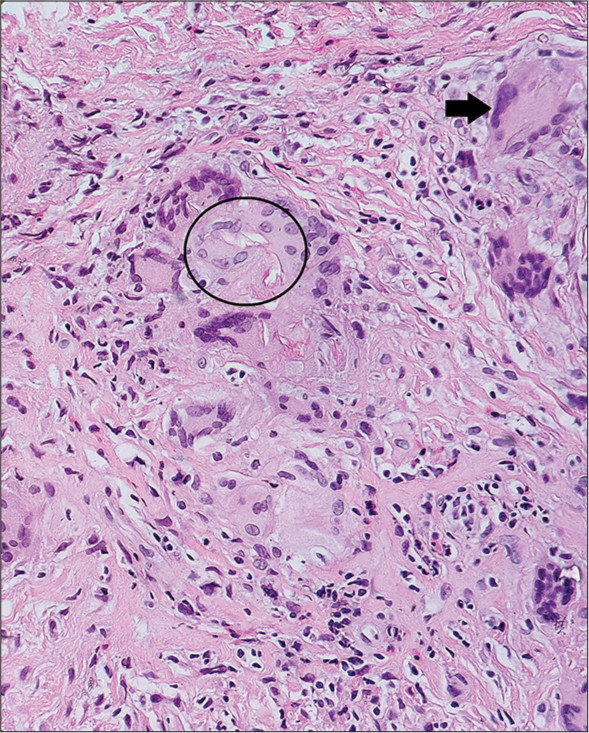

The smear from the ulcer showed pauci-septate thin-walled hyaline hyphae on potassium hydroxide mount. Histopathology revealed epitheloid cell granulomas, along with multinucleated giant cells, lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, and a few eosinophils involving deep dermis and subcutaneous tissue. Areas of fat necrosis and giant cells showing weakly hematoxyphilic pauci-septate, thin-walled branching hyphae, and spherical fungal elements were also noted [Figure 2]. Periodic acid Schiff and Gomori methenamine silver stains confirmed the presence of fungal hyphae [Figure 3]. The fungal culture showed broad pauciseptate hyaline hyphae with sporangia elongated with beaking and zygospores rounded with beak-like remnants suggestive of Basidiobolus species.

- Mid dermis showing epithelioid cell granulomas composed of Langhans giant cells (arrow), lymphocytes, plasma cells, histiocytes, and a few eosinophils—areas of giant cells showing weakly hematoxyphilic pauci-septate hyphae (circle).

- Giant cells showing few hyphae. Grocott–Gomori’s methenamine silver stain highlights fungal hyphae (circle).

She was started on oral itraconazole 200 mg twice daily and a saturated solution of potassium iodide (SSKI). SSKI was started at the dose of five drops thrice daily, and the number of drops increased to 20 drops. Significant reduction in size was noticed, but the patient discontinued treatment after few months. After eight months, lesions relapsed as multiple freely mobile subcutaneous nodules over the same sites varying in size from 2 × 2 cm to 4 × 5 cm, with no ulceration or pus discharge. She was started on voriconazole 800 mg loading dose followed by 200 mg twice daily. However, two days later, she developed hyponatremia and a seizure episode, prompting withdrawal of voriconazole. The patient was restarted on oral itraconazole. Injection amphotericin-B 50 mg (0.8 mg/kg) was added, but no response was noted even after 15 days of therapy. Hence, extensive mechanical debridement was tried, cotrimoxazole 800/160 mg daily was started in view of its antibacterial and fungistatic action, and itraconazole and amphotericin were discontinued. After 6–12 weeks of therapy, a significant reduction in ulcer size was noted and healthy granulation tissue developed [Figure 4].

- Reduction in the size of the ulcer at the end of 3 months of combined surgical and cotrimoxazole therapy.

Basidiobolomycosis is a chronic fungal infection of subcutaneous tissue found in immunocompetent patients. The disease is mostly limited to tropical and subtropical regions. The subcutaneous tissue of the thigh, trunk, and buttocks are the common sites; rarely, other parts of the body, such as the face and nose, also may be involved.[1] Most of the cases of basidiobolomycosis respond well to oral itraconazole[2] and/or saturated salt solution of potassium iodide.[3] In resistant cases, voriconazole has been tried.[4]

The dose of oral itraconazole in cutaneous and gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis is usually 5 mg/kg. Although the response is noted in 2 weeks, prolonged therapy is needed.[5,6] Vikram et al. described that 73% of cases with basidiobolomycosis receiving oral itraconazole had a good response.[7] Our case showed significant improvement with oral itraconazole 5 mg/kg/day and SSKI, as evidenced by the decrease in size of the ulcers and nodules. However, after some time patient relapsed either due to premature withdrawal of treatment or drug resistance. Relapse and extensive lesion of the patient compelled us to shift to voriconazole.

Voriconazole has been used as second line azole for basidiobolomycosis resistant to itraconazole.[4,8] Although rare, hyponatremia is a dangerous adverse effect of voriconazole. As our patient developed severe hyponatremia and seizure, the drug had to be stopped.

Surgical intervention in combination with systemic therapy is preferred in extensive disease.[7] Among other treatment modalities, Al-Qahtani et al. reported significant fungistatic properties of non-antifungal agents cotrimoxazole, chloramphenicol, and artesunate against Basidiobolus species. They have also reported significant synergistic effects of cotrimoxazole with voriconazole and artesunate with voriconazole in vitro.[9]

Our case was unusual as it was extensive, presented with ulcerations, and had a poor response to classical therapy.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

References

- Basidiobolomycosis of the nose and face: A case report and a mini-review of unusual cases of basidiobolomycosis. Mycopathologia. 2010;170:165-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Successful treatment of extensive basidiobolomycosis with oral itraconazole in a child. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:572-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subcutaneous zygomycosis: A report of one case responding excellently to potassium iodide. Indian J Dermatol. 2015;60:500-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- A case report of gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis treated with voriconazole: A rare emerging entity. Medicine (Baltimore). 2015;94:e1430.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis. J Pediatr Surg Case Reports. 2020;55:101411.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Invasive basidiobolomycosis presenting as retroperitoneal fibrosis: A case report. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:535.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emergence of gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis in the United States, with a review of worldwide cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1685-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Successful treatment of gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis with voriconazole without surgical intervention. J Trop Pediatr. 2014;60:476-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antifungal activities of artesunate, chloramphenicol, and cotrimoxazole against Basidiobolus species, the causal agents of gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis. bioRxiv 2021:2021-01.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]