Translate this page into:

Cutaneous abscess: Unveiling the mystery

*Corresponding author: K. Krishna Mohan, Senior Resident, Department of Dermatology, Government Medical College, Ernakulam, Kerala, India. krishna.mohan.k1914@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Mohan KK, Augustine D, Preethi K, Manju M, Panikulam NJ. Cutaneous abscess: Unveiling the mystery. J Skin Sex Transm Dis 2020;2(2):126-9.

Abstract

Disseminated Nocardia infection is uncommon in clinical practice, with most cases occurring as opportunistic infections in immunocompromised patients. Cutaneous nocardiosis is often misdiagnosed because of its rarity and nonspecific clinical picture. Here, we report a case of disseminated nocardiosis in an immunocompetent patient presenting with multiple cutaneous abscesses.

Keywords

Disseminated nocardiosis

Nocardia

Cutaneous abscess

Immunocompromised

INTRODUCTION

The genus Nocardia belongs to the order Actinomycetales. It is aerobic, Gram-positive, filamentous bacteria. The organism is mainly geophilic and occurs in soil and decaying plant parts. Nocardia brasiliensis is the main pathogenic organism for primary cutaneous infection. N. asteroides usually causes fulminant systemic infection.[1] Immunocompromised patients account for 50% of cases, mostly pulmonary, systemic, and CNS infections.[2] Primary cutaneous disease is most commonly seen in immunocompetent patients.[1] Skin lesions are seen in 10% of patients with disseminated nocardiosis. The most common cutaneous manifestations in disseminated nocardiosis are pustules, abscesses, and nodules, which are frequently ulcerated.[3] Disseminated nocardiosis is rarely reported in immunocompetent individuals. Here, we are presenting a 54-year-old immunocompetent male patient with disseminated nocardiosis affecting lungs, CNS, and skin.

CASE REPORT

A 54-year-old male was admitted in medical ward with complaints of fever, cough, hemoptysis, anorexia, and weight loss for the past 2 weeks. The patient had a history of pulmonary tuberculosis 8 years ago for which he took antituberculous treatment (ATT) for 4 months and stopped by himself. No other comorbidities were present and he was otherwise healthy. He was not on any immunosuppressants or systemic corticosteroids. Sputum AFB was 3+. The patient was started on ATT with a diagnosis of reactivation of old pulmonary tuberculosis.

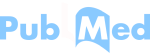

On the 5th day of admission, the patient developed irrelevant talks, disorientation, vomiting, neck stiffness, involuntary passage of urine, and stool. Due to worsening respiratory symptoms and signs, the patient was shifted to ICU [Figure 1]. Differential diagnosis of tuberculous meningitis, multidrug-resistant tuberculosis, and hyponatremia were considered.

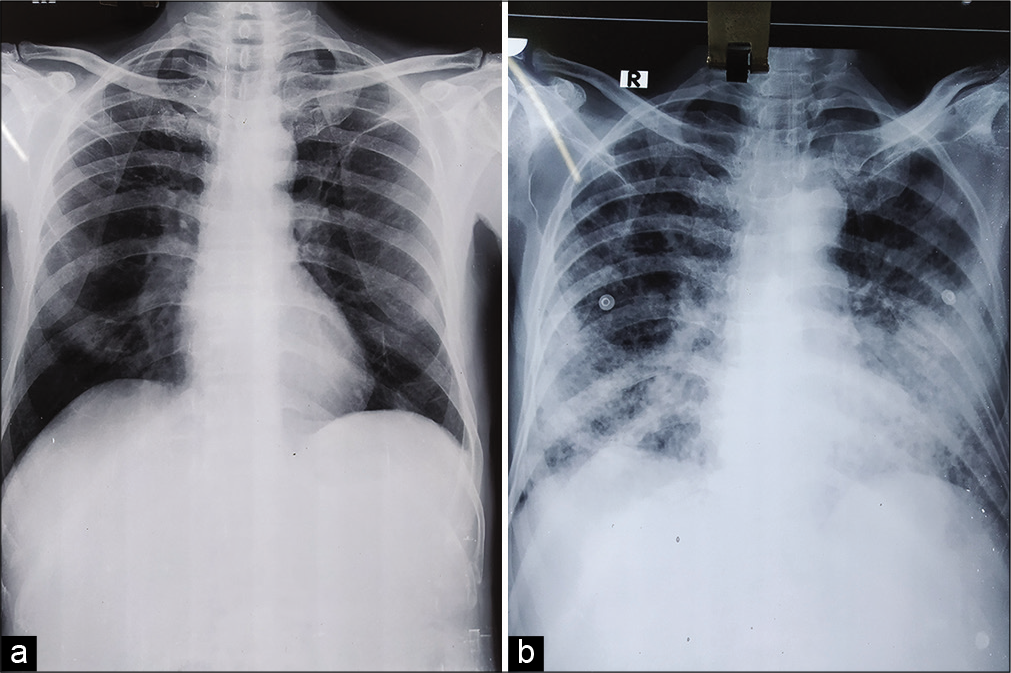

On the 8th day of admission, dermatology opinion was sought for two fluctuant swellings on the right side of chest [Figure 2]. Tenderness could not be elicited as the patient was unconscious. There was no local rise in temperature. Thick pus aspirated from the lesions was sent for Gram stain, AFB stain, and culture. Differential diagnosis considered were tuberculous cold abscess, septicemia, and systemic nocardiosis.

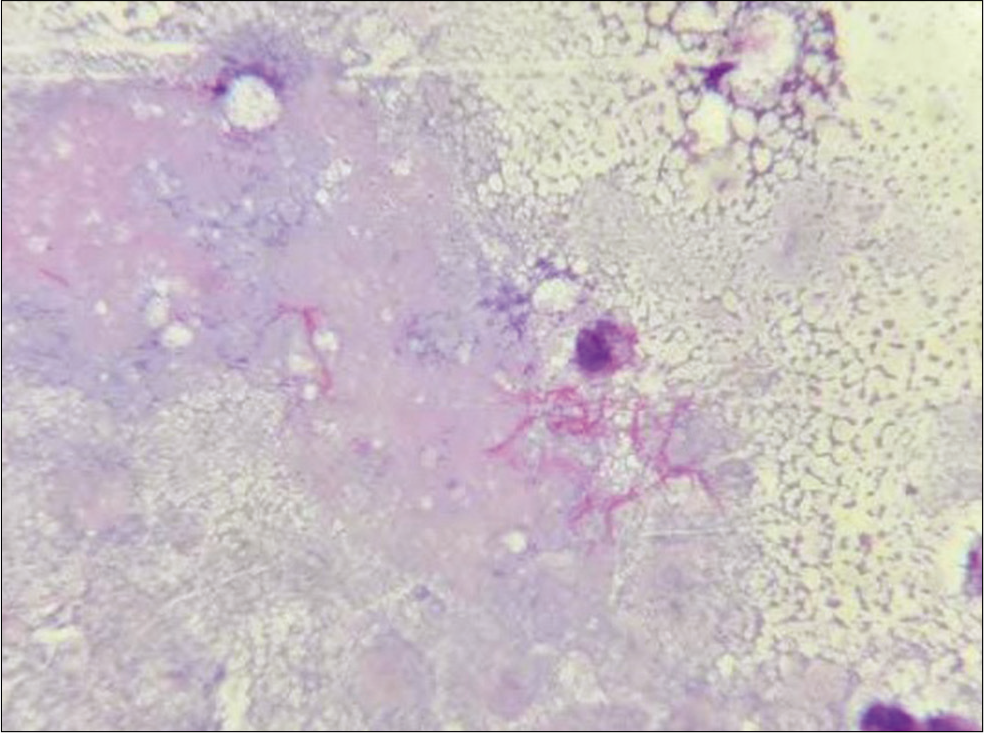

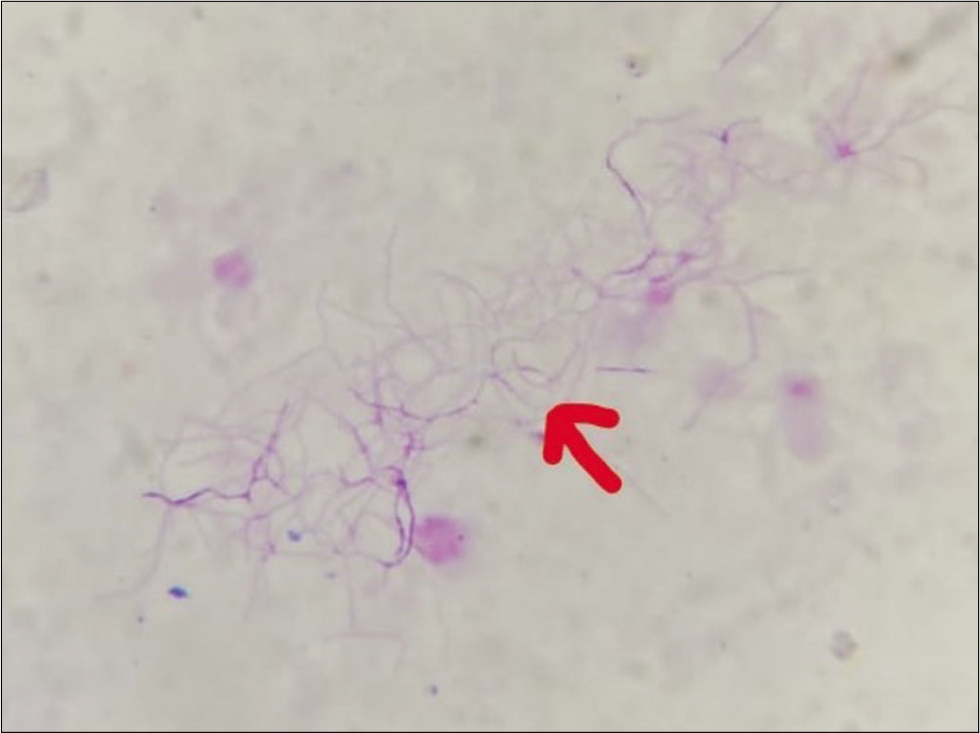

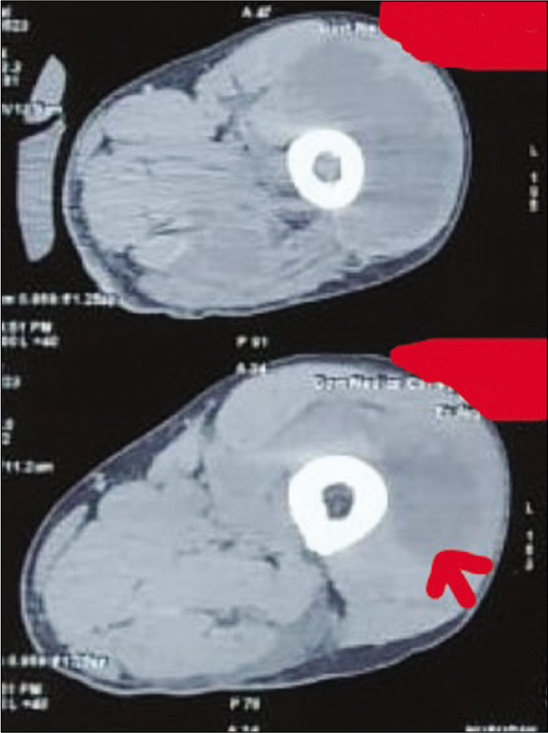

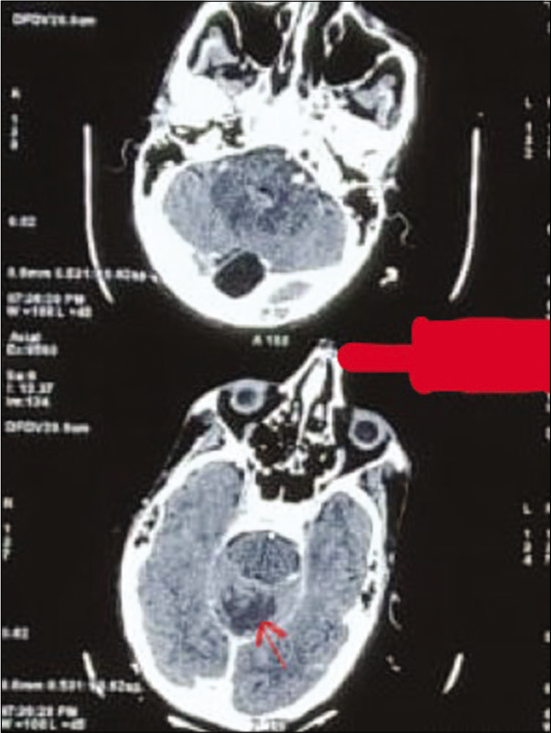

Gram stain from the pus showed thin filamentous beaded Gram-positive bacilli [Figure 3]. Modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain showed AFB-positive bacilli [Figure 4]. Culture of pus on blood agar revealed chalky white cotton candy appearance of colonies suggestive of growth of Nocardia species [Figure 5]. CBNAAT done on sputum and gastric aspirate samples were negative for mycobacterium tuberculosis. Modified Ziehl-Neelsen staining of gastric aspirate showed thin filamentous beaded acid-fast bacilli suggestive of Nocardia species. Blood culture demonstrated growth of Nocardia species. HIV test done was negative. CT done for swelling and tenderness over the left thigh showed intramuscular collection in anterior and lateral compartment possibly abscess [Figure 6]. CT brain showed ill-defined hypodensity in the cerebellar vermis possibly due to infective/inflammatory etiology [Figure 7]. CSF study revealed lymphocytic pleocytosis with hypoglycorrhachia suggestive of meningitis of infectious etiology [Table 1]. CSF culture was negative. Although the classical CSF findings in nocardial meningitis are neutrophilic pleocytosis, hypoglycorrhachia, and elevated protein levels, lymphocytic pleocytosis is also rarely reported.[4] The possibility of nocardial meningitis was considered here in view of the culture from cutaneous lesion isolating Nocardia, CSF study indicating meningitis of infective origin, and the laboratory parameters ruling out the other probable differential diagnosis.

With these investigation reports, diagnosis was revised as systemic nocardiosis. ATT was stopped and the patient was started on doxycycline 100 mg twice daily per orally, cotrimoxazole double strength twice daily per orally and streptomycin 0.5gm once daily intramuscularly. The patient succumbed to the infection in spite of treatment.

- (a) Initial chest X ray showing ill-defined patchy opacity in the right lower zone, (b) chest X ray after 5 days showing ill-defined opacities in the right lower zone and alveolar opacities in the left lower zone.

- Cutaneous abscess (red arrow).

- Pus aspirated from cutaneous swellings showing thin filamentous beaded Gram-positive bacilli (Gram stain, ×1000).

- Pus aspirated from cutaneous swellings showing (red arrow) acid-fast bacilli (modified Ziehl-Neelsen stain, ×1000).

| Total count | 25 cells/mm3 |

|---|---|

| Differential count – neutrophil | 3 cells/mm3 |

| Lymphocyte | 22 cells/mm3 |

| RBC | 2–6/hpf |

| CSF protein | 227 mg/dl |

| CSF sugar | 40 mg/dl |

| RBS | 144 mg/dl |

| LDH | 314 µ/l |

| ADA | 9.45 µ/l |

DISCUSSION

The major risk factor for Nocardia infection is being immunocompromised with cell-mediated immunity defects.[2] Nocardiosis presents as either pulmonary, cutaneous, or disseminated disease. Pulmonary nocardiosis is the most common manifestation of nocardiosis and is acquired through the inhalation of the organism from dust or soil.[5] Pulmonary involvement is associated with pneumonia, empyema, or lung abscesses. About 50% of all pulmonary cases disseminate to extrapulmonary sites, most commonly to the brain.[2]

Disseminated disease is defined by the presence of two or more organs infected by Nocardia. Disseminated nocardiosis is characterized by hematogenous spread of microbes to brain, eye, bone, joint, heart, kidney, skin, or other organs and tissues.[6] Nocardiosis has the ability to disseminate to any organ and has a tendency to relapse or progress despite being given the appropriate therapy. Most common site affected is CNS.[7] The clinical picture may closely simulate pulmonary or meningeal tuberculosis. In 75% of cases, pulmonary involvement with cough, dyspnea, hemoptysis, and fever occurs.[8,9] The presence of simultaneous lung and brain abscesses is a reliable indication of an underlying Nocardia infection.[10] If left untreated, disseminated nocardiosis has a mortality rate of greater than 85%.[2]

Cutaneous nocardiosis can occur in two ways – either as a part of disseminated infection or as a primary infection resulting from inoculation. Primary cutaneous nocardiosis is relatively rare.[1] The mode of transmission is accidental inoculation. The three major forms of primary cutaneous nocardiosis are (1) mycetoma, (2) lymphocutaneous nocardiosis, and (3) superficial cutaneous nocardiosis.[1] Skin lesions are seen in 10% of patients with disseminated nocardiosis. The most common cutaneous manifestations are pustules, abscesses, and nodules which are frequently ulcerated. The pustules are generally larger than pustules of steroid-induced acne, candidal folliculitis, or staphylococcal folliculitis. The most common sites affected are the trunk and proximal extremities.[3]

- Culture of pus on blood agar showing chalky white cotton candy appearance of Nocardia colonies.

- Computed tomography showing intramuscular collection (red arrow) in anterior and lateral compartment of the left thigh.

- Computed tomography brain showing ill-defined hypodensity (red arrow) in the cerebellar vermis.

Gram staining is the most sensitive method for visualizing Nocardia.[2] Nocardia is partially acid fast by conventional Ziehl-Neelsen staining and is reactive with Gomori methenamine silver.[2] Organisms are detected as Gram-positive, branched filamentous hyphae and branching at right angles is diagnostic, cultures should be kept for up to 2–3 weeks for isolation. The microorganisms grow satisfactorily on most of the nonselective media used for isolation of bacteria, mycobacterium, and fungi. After initial isolation, subcultures should be incubated at 25°C, 35°C, and 45°C. N. asteroides grows best at 35°C. Aerial hyphae giving a chalky appearance may be seen macroscopically in cultures.[11] Western blot assay, using monoclonal antibodies against 54 kDa circulating antigens of Nocardia, and species-specific DNA probing help in the rapid and definitive diagnosis of nocardiosis. ELISA for serodiagnosis of nocardial infection is also useful.[1]

In general, the antibacterial agents most active against N. asteroids are the sulfonamides, amikacin, minocycline, and imipenem. Treatment for immunocompetent patients should be for at least 6 months. Treatment for disseminated Nocardia will depend on the presence or absence of CNS involvement and/or multiple organ involvement. If the central nervous system is involved, treatment for 12 months is recommended.[2] Patients with primary cutaneous nocardiosis respond very well to cotrimoxazole.[1]

CONCLUSION

It was the presence of multiple cutaneous abscesses which led to the revised diagnosis of systemic nocardiosis in this case. This highlights that the possibility of systemic nocardiosis should be considered in every patient presenting with cutaneous abscess with systemic symptoms related to respiratory system or nervous system. This patient was immunocompetent which indicates that systemic nocardiosis can rarely occur even in immunocompetent individuals.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Primary cutaneous nocardiosis: A case study and review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2003;69:386-91.

- [Google Scholar]

- A complicated case of an immunocompetent patient with disseminated nocardiosis. Infect Dis Rep. 2014;6:5327.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Cutaneous nocardiosis: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2010;49:1380-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nocardial meningitis: Case reports and review. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13:160-5.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Pulmonary nocardiosis due to Nocardia otitidiscaviarum in an immunocompetent host-a rare case report. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2011;4:414-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nocardia spp infections among hematological patients: Results of a retrospective multicenter study. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e610-4.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nocardia species: Host-parasite relationships. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1994;7:213-64.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nocardial infections in the immunocompromised host: A detailed study in a defined population. Rev Infect Dis. 1981;3:492-507.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Nocardiosis: Updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection. 2010;38:89-97.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A case of systemic nocardiosis in systemic vasculitis and a review of the literature. Singapore Med J. 2013;54:e127-30.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A case series and focused review of nocardiosis: Clinical and microbiologic aspects. Medicine (Baltimore). 2004;83:300-13.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]