Translate this page into:

Reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption: A case report

*Corresponding author: Arunprasath Palanisamy, Department of Dermatology, Nandha Medical College and Hospital, Erode, Tamil Nadu, India. drmuhil_irt@yahoo.co.in

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Palanisamy A. Reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption: A case report. J Skin Sex Transm Dis. doi: 10.25259/ JSSTD_85_2024

Abstract

A 26-year-old male was evaluated for oral and genital mucosal erosions, vesiculobullous lesions in the palms, and targetoid lesions involving the lower legs, which he had for one month. Diagnostic evaluation revealed an elevated C-reactive protein and positive Mycoplasma pneumoniae immunoglobulin. A diagnosis of reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption was made. He was treated with oral azithromycin and tapering doses of oral steroids with resolution of skin lesions in two weeks.

Keywords

Mucocutaneous eruptions

Mycoplasma pneumonia

Mycoplasma pneumonia-induced rash and mucositis

Reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption

INTRODUCTION

Mucocutaneous eruptions are lesions that involve both skin and mucous membranes. Based on the history, clinical morphology, and underlying etiology like infections or drugs, mucocutaneous eruptions can be typified into different conditions such as erythema multiforme (EMF), Stevens-Johnson syndrome (SJS), toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN), and drug reaction with eosinophilia and systemic symptoms.[1] Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis (MIRM) and, recently, reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption (RIME) are additions to mucocutaneous eruptions occurring secondary to infections. This case report describes a case of RIME in a 26-year-old male.

CASE REPORT

A 26-year-old male presented with complaints of oral and genital lesions for one month. He also had fluid-filled lesions in the right palm and reddish-raised skin lesions in the legs. He did not have any fever or cough. There was no history of any sexual contact or drug intake before the onset of lesions. Furthermore, there was no history of similar skin lesions in the past.

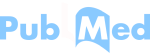

Cutaneous examination revealed erythematous vesiculobullous lesions involving the right palm [Figure 1a] and a few erythematous plaques, targetoid lesions, and vesicles in both legs [Figures 1b and c]. Oral cavity examination displayed hemorrhagic crusts in the lower lip and erosions involving the gingiva, buccal mucosa, and the tongue [Figure 2a and b]. Examination of the genitalia showed erosions involving the glans, coronal sulcus, and prepuce [Figure 3]. There was no inguinal adenopathy or urethral discharge. Systemic examination was essentially normal.

- (a): Erythematous vesiculobullous lesions involving the right palm; (b and c): targetoid lesions and discrete vesicles involving the legs.

- (a): Hemorrhagic crusts in the lower lip and erosions involving the labial and gingival mucosa; (b): erosions in the buccal mucosa, palate and tongue.

- Erosions involving the glans, coronal sulcus, and prepuce.

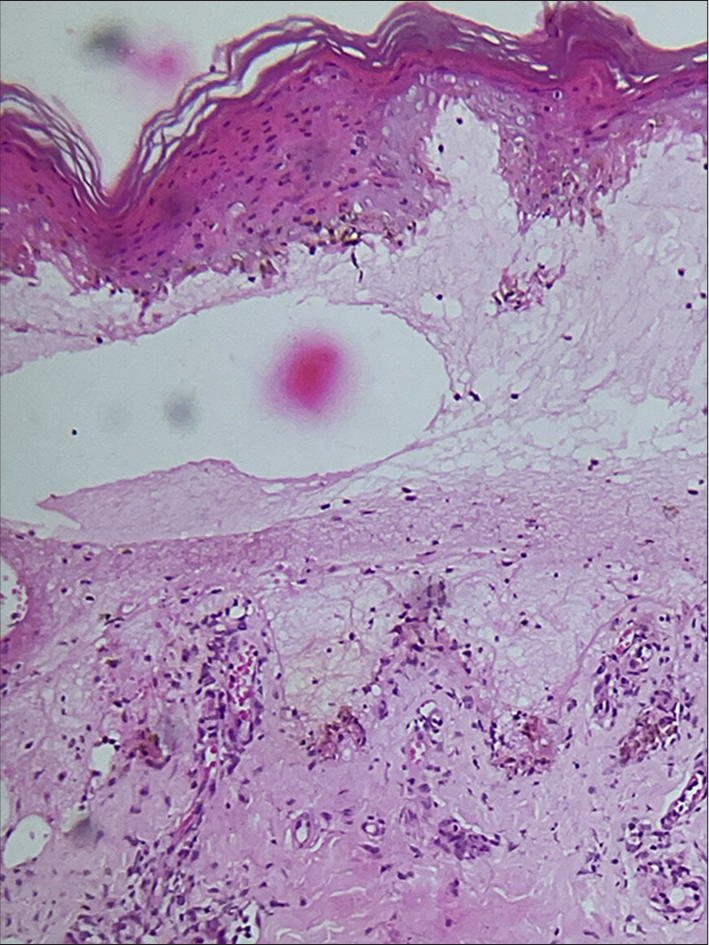

Routine investigations, including complete hemogram, renal function tests, and liver function tests, were within normal limits. C-reactive protein was high (96 mg/dL; Positive: >6 mg/dL), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate was elevated (52 mm/h). Screening for human immunodeficiency virus 1 and 2 was negative, and Venereal Disease Research Laboratory was non-reactive. Serology for herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 immunoglobulin M (IgM) and immunoglobulin G was not contributory. Chest skiagram was normal. M. pneumoniae IgM was positive (10.20, reference range positive >8.80). Histopathological examination of the biopsy obtained from a targetoid lesion involving the right leg revealed subepidermal bullae with dermal edema and intense dermal inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes around superficial dermal vessels and adnexal structures [Figure 4].

- Subepidermal bulla with dermal edema with perivascular and periadnexal dermal inflammatory infiltrate composed of lymphocytes and histiocytes (Hematoxylin & eosin, ×100).

Based on clinical features, histopathology, and positive M. pneumoniae serology, a diagnosis of RIME was made. He was treated with azithromycin 500 mg for five days along with a short course of tapering doses of prednisolone with complete resolution of skin lesions in two weeks.

DISCUSSION

Canavan et al. described MIRM as a distinct clinical entity involving young patients with prominent mucosal involvement, sparse cutaneous involvement, and excellent prognosis.[2] The cutaneous lesions can present as erythematous macules, atypical target lesions, targetoid, and vesiculobullous lesions, predominantly involving the acral areas. Mucosal lesions can involve oral, ocular, and urogenital mucosa.[2]

RIME is eruptive mucositis with varying degrees of cutaneous involvement due to an immunologic response to various infectious pathogens.[3] Ramien had reported that apart from M. pneumoniae, other infectious triggers such as Chlamydia pneumoniae, influenza B, enterovirus, rhinovirus, human metapneumovirus, human parainfluenzavirus, varicella-zoster virus, hepatitis A, Epstein–Barr virus, Merkel cell polyomavirus, cytomegalovirus, and human herpes virus-6 can cause clinical picture akin to MIRM, which made them propose the term RIME, which would include MIRM as well.[4] Recently, there have been multiple reports of “reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption” associated with COVID-19 infection.[5] Sanfilippo et al. described a case of RIME due to norovirus.[3]

Martinez-Cabriales et al., in their “PROMISE” study, had reclassified various blistering, severe cutaneous adverse reactions such as SJS, TEN, EMF major, MIRM, and Fuchs syndrome into two broad categories: RIME and drug-induced epidermal necrolysis (DEN). In RIME cases, M. pneumoniae was the major pathogen implicated, and in DEN cases, anticonvulsants were the most common drug involved.[6]

Treatment options for RIME include mucosal care, maintenance of fluid and electrolyte abnormalities secondary to reduced oral intake if any, antimicrobials, and antivirals based on underlying infectious triggers. Macrolides such as azithromycin, clarithromycin or erythromycin, doxycycline, and levofloxacin can be used if the underlying infection is M. pneumoniae.4 In case of extensive mucosal involvement, immunomodulatory therapies, including systemic corticosteroids, intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, or tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, can be considered on a case-to-case basis.[4,5,7]

CONCLUSION

To conclude, mucocutaneous eruptions in a young adult with severe mucosal involvement and discrete cutaneous involvement should be evaluated for RIME, as early diagnosis and appropriate treatment will mitigate the suffering of the patient. It is also prudent from the above discussion that the term RIME would be more appropriate than MIRM, even in patients with underlying M. pneumoniae infection.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The author certifies that he has obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript, and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- Mycoplasma pneumonia-induced rash and mucositis (MIRM) In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30247835/

- [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis as a syndrome distinct from Stevens-Johnson syndrome and erythema multiforme: A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:239-45.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Severe reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption mimicking drug-induced epidermal necrolysis triggered by norovirus. Pediatr Dermatol. 2024;41:84-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption: Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis and other parainfectious eruptions. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2021;46:420-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption secondary to COVID-19 infection: A case report and review of the literature. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38:e204-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preliminary summary and reclassification of cases from the pediatric research of management in Stevens-Johnson syndrome and epidermonecrolysis (PROMISE) study: A North American, multisite retrospective cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:635-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evaluation of etanercept for treatment of reactive infectious mucocutaneous eruption. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157:230-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]