Translate this page into:

Coexistence of multiple sexually transmitted infections in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative individual

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Augustine D, James A, Preethi K. Coexistence of multiple sexually transmitted infections in a human immunodeficiency virus-negative individual. J Skin Sex Transm Dis 2022;4:127-31.

Abstract

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are a major public health problem for men and women worldwide as they cause acute disease as well as a long-term complications, if left untreated. We report a young migrant laborer with high-risk, sexual behavior who presented with asymptomatic, warty papules of penile shaft of 3 months duration, multiple asymptomatic penile ulcers of 10 days, and yellowish creamy discharge per urethra of 1 week duration. Clinical evaluation and investigations confirmed the diagnosis of coexisting primary syphilis (chancre), acute gonococcal urethritis, genital wart, and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection. Serology for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection was negative. He was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice a day per orally for 14 days (for primary syphilis), ceftriaxone 250 mg single-dose intramuscularly (for gonococcal urethritis), azithromycin 1 g single dose per orally and topical 25% podophyllin in tincture benzoin (applied by the clinician for genital wart). He was referred to the department of general medicine for further evaluation and management in view of the positive serology for anti-HCV antibodies. We report this case to highlight the rare coexistence of multiple STIs in an HIV-negative patient.

Keywords

Gonorrhea

Chancre

Condylomata acuminata

Hepatitis C virus infection

INTRODUCTION

Sexually transmitted infections (STIs) contribute to a significant portion of the public health burden globally. In 2016, the World Health Organization estimated 376 million new infections with one of the four STIs: Gonorrhea (87 million), syphilis (6.3 million), chlamydial urethritis/ cervicitis (127 million), and trichomoniasis (156 million).[1] More than 120 distinct subtypes of the human papilloma virus (HPV) have been identified. Of these 120 HPVs, 40 are capable of infecting the anogenital tract. Infection by high-risk HPV is identified as an important cause of cervical cancer.[2]

STIs also increase the risk of acquisition and transmission of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).[3] Herein, we report a young man who manifested coexistence of acute gonococcal urethritis, primary syphilis, genital warts, and positive serology for hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

CASE REPORT

A 24-year-old, unmarried, male, migrant laborer presented to our outpatient department with a history of asymptomatic, warty lesions (about 90 days) and multiple, painless ulcers on the shaft of the penis (10 days), and yellowish creamy discharge per urethra (7 days). He had no constitutional symptoms. He did not give any history of dysuria or frequency of micturition.

The patient gave a history of multiple, unprotected, and heterosexual contacts with multiple partners including commercial sex workers over the past 4 years. He did not give any history of homosexual exposure. He gave no history of oral or anal sex. He gave a history of intravenous drug use for 4 years.

General examination revealed mobile, firm, and non-tender inguinal, and epitrochlear lymphadenopathy on both sides (ranging in size from 0.5 × 0.5 cm to 1.5 × 1.5 cm). There were multiple, hyperpigmented scars of needle punctures on both cubital fossae.

Examination of genitalia revealed copious, purulent, and yellowish discharge at the tip of the external urethral meatus without any edema and erythema of meatus [Figure 1].

- Copious, purulent, and yellowish discharge at the tip of external urethral meatus without any edema and erythema of meatus.

Two well-defined, non-tender, genital ulcers were present on the anterior and posterior aspects of the lower part of the shaft of the penis, respectively. One of the ulcers showed serous discharge [Figure 2], while the other one was covered with dried exudate. Both had a button-like consistency and were of size 0.5 × 0.5 cm.

- Non-tender genital ulcer of size 0.5 × 0.5 cm covered with serous exudate on the posterior aspect of the lower part of shaft of penis.

There were multiple, discrete, and warty papules of size 0.3 × 0.3 cm on the shaft of the penis [Figure 3]. He did not show similar lesions on other body sites.

- Multiple, discrete, and warty papules of size 0.3 × 0.3 cm on the shaft of penis.

We did not notice any other lesion on the glans penis, prepuce, scrotum, or perianal area. Systemic examination was within normal limits.

Based on the history and clinical examination, we made a provisional diagnosis of primary chancre with acute urethritis and “papular” genital warts.[4]

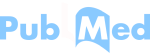

Gram stain of urethral smear and urine sediment showed neutrophils with Gram-negative, intracellular, and reniform diplococci [Figure 4].

- Gram stain of urethral smear. Red arrow indicates neutrophils with Gram-negative, intracellular and reniform diplococci (Gram stain, ×1000).

Dark-field microscopy of serous exudate from the penile ulcer did not reveal any organism. Smear from the ulcers did not show any multinucleated giant cells on Tzanck smear or any organisms on Gram stain.

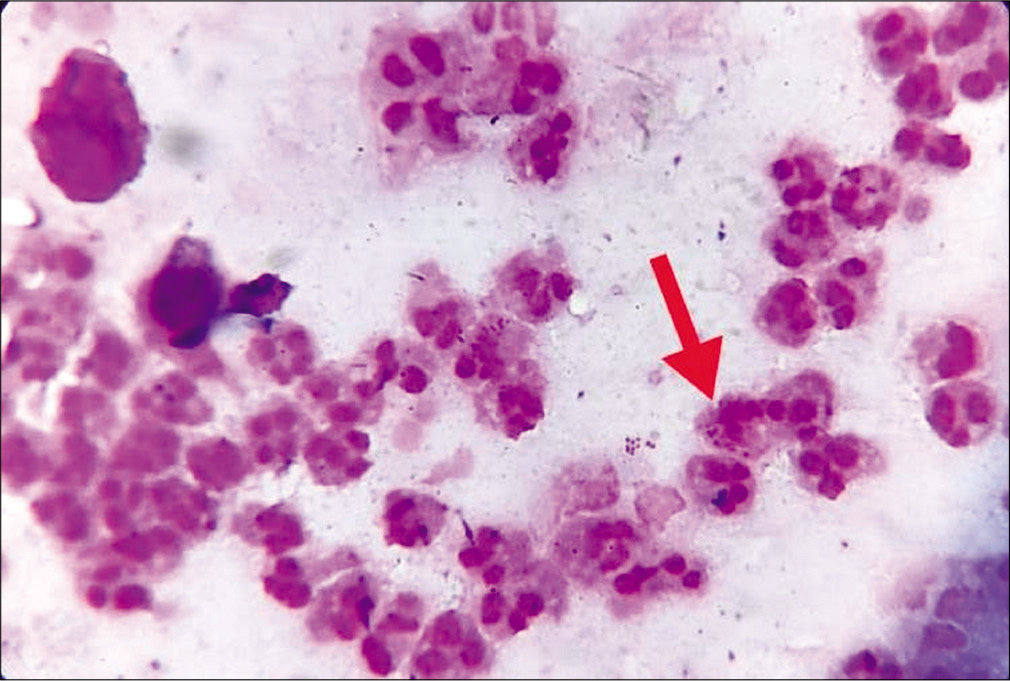

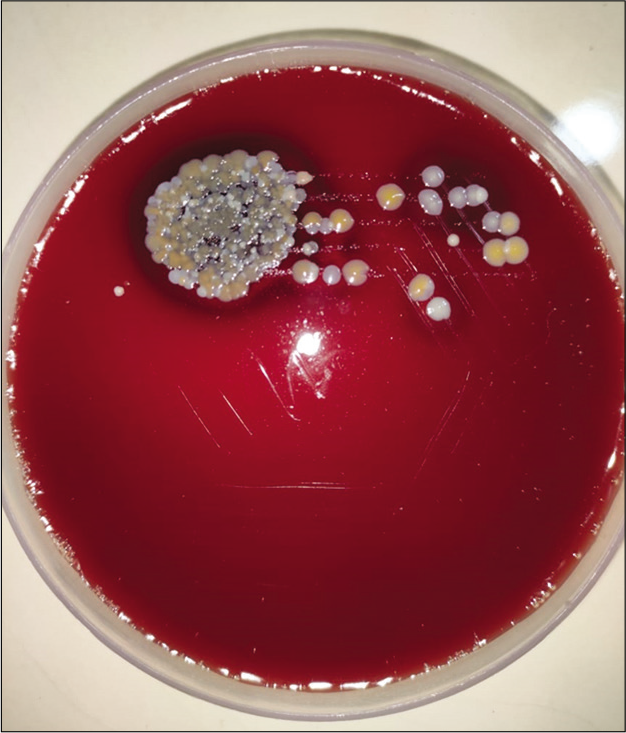

Complete hemogram was within normal limits. Venereal disease research laboratory test (VDRL) was reactive in 1:128 titer. Treponema pallidum hemagglutination test (TPHA) was reactive in 1:2560 dilution. Serology was positive for anti-HCV antibody, but negative for anti-HIV antibody and hepatitis B surface antigen. Culture and sensitivity of urethral discharge revealed colonies of gonococci on blood agar and chocolate agar [Figures 5 and 6] with positive catalase and oxidase tests.[5,6]

- Blood agar showing colonies of gonococci.

- Chocolate agar showing colonies of gonococci.

Thus, a final diagnosis of primary syphilis, acute gonococcal urethritis, genital wart, and HCV infection was made. As the patient refused parenteral benzathine penicillin, he was treated with doxycycline 100 mg twice a day per orally for 14 days.[7] Gonorrhea was treated with ceftriaxone 250 mg intramuscularly single dose and 1 g azithromycin per orally single dose.[8-10] For genital warts, he received topical application of 25% podophyllin in tincture benzoin which was applied by the clinician. He was informed of the need to repeat the treatment with podophyllin weekly till the complete resolution of warts.[11]

He received counseling regarding safe sex practices. He was referred to the department of general medicine for further evaluation and management since he showed serological positivity for anti-HCV antibodies.[12,13] We also referred him to the psychiatry department for deaddiction services.

The patient left for his native place after receiving the diagnosis and initial treatment at our institution and was lost to follow-up. We were unable to contact his partners since he was reluctant to divulge any information regarding them.

DISCUSSION

The coexistence of multiple STIs is not uncommon in patients attending STI clinics. Choudhary et al., reported multiple STIs in 37% of STI clinic attendees.[14] Our patient manifested coexistence of chancre, gonococcal urethritis, and genital wart, and a positive serology for anti-HCV antibody (another infection that has a possible sexual mode of transmission).

Many STIs are often asymptomatic in their initial stages; hence, it is likely that a coinfecting STI may be missed, if not properly evaluated. A patient with STI should be examined and evaluated in detail to rule out any coexisting STIs to ensure adequate and effective treatment.

We added azithromycin to the treatment regimen since gonococcal urethritis is often accompanied by chlamydial infection and we did not have the facility to rule out a coexisting chlamydial infection by nucleic acid amplification test.[8]

Negative dark-field microscopy in our patient was not against the possibility of chancre since the sensitivity of the same to detect Treponema pallidum varies from 71 to 90%.[15] The reactive VDRL and TPHA tests along with the history, clinical features, and the information obtained from Tzanck smear and Gram stain analysis were in favor of primary chancre in our patient.[7] Multiple chancres, as observed in our case, though not common, are well reported in the literature.[16]

Although the terminology “condylomata acuminata” is often used as a synonym for genital warts, four different morphological types are described for warts affecting the genitalia. They include the fleshy, moist, cauliflower-like growths known as condylomata acuminata, flesh-colored, dome-shaped papules called papular warts, keratotic warts manifesting a thick crust-like layer, and flat-topped papules that may appear macular or slightly raised. Hence, we preferred to use the term genital warts instead of “condylomata acuminata” for the papular warts observed in our case. We believe that they belong to the morphological type of “papular warts.”[4]

HCV infection is mostly considered a blood-borne disease with less efficient transmission through sexual contact. High-risk traumatic sexual acts, presence of concurrent genital ulcer disease, group sex, use of cocaine, and other non-intravenous drugs during sex and multiple sex partners in the setting of pre-existing HIV and MSM (male sex with male) are mentioned as risk factors for sexual transmission of HCV. Our patient had concurrent genital ulcer disease, which is considered as a risk factor for the sexual transmission of HCV. However, intravenous drug use is mentioned as an independent risk factor for HCV transmission. Given the intravenous drug use, a non-sexual mode of transmission cannot be ruled out for HCV in our patient.[12]

Positive serology for anti-HCV antibody noted in our case warranted further evaluation to distinguish between an active and a past infection. Chronic HCV infection may lead to chronic liver disease, and autoimmune manifestations such as vasculitis and lymphomas.[17] Nucleic acid amplification test or reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction assay for HCV RNA may help to differentiate an active HCV infection from a past infection. This has become important, since the introduction of drugs such as sofosbuvir and daclatasvir has revolutionized the treatment of HCV infection by offering a cure rate of 95%.[17] Although we referred the patient to the department of general medicine for a detailed evaluation on the status of HCV infection and to assess the need for further treatment, he preferred to return to his native place.

CONCLUSION

The coexistence of multiple STIs in our patient (who was HIV negative) points to the importance of a detailed evaluation to detect coexisting STIs among STI clinic attendees. This also highlights the importance of education regarding safe sex practices among high-risk groups.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- Chlamydia, gonorrhoea, trichomoniasis, and syphilis: Global prevalence and incidence estimates, 2016. Bull World Health Organ. 2019;97:548-62.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genital ulcer disease treatment for reducing sexual acquisition of HIV. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;8:CD007933.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heterosexual risk of HIV 1 infection per sexual act: Systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. Lancet Infect Dis. 2009;9:118-29.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Genital human papilloma virus infection In: Holmes KK, Sparling PF, Stamm WE, Piot P, Wasserheit GN, Corey L, eds. Sexually Transmitted Diseases (4th ed). New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. p. :489-508.

- [Google Scholar]

- Superoxol (catalase) test for identification of Neisseria gonorrhoeae. J Clin Microbiol. 1982;15:475-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/gonorrhea/lab/ngon.htm [Last reviewed on 2017 Mar 31]

- Diseases characterized by urethritis and cervicitis. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:60-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human papilloma virus infections. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2021;70:100-13.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. ;64(2015):1-137.

- [Google Scholar]

- Update on the management and treatment of viral hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:3249-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Characterization of patients with multiple sexually transmitted infections: A hospital-based survey. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2010;31:87-91.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sexually acquired syphilis: Laboratory diagnosis, management, and prevention. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:17-28.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Multiple primary penile chancre: A re-emphasize. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2014;35:71-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Update on the management and treatment of viral hepatitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2021;27:3249-61.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]