Translate this page into:

Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata in a newborn: A case report and review of literature

*Corresponding author: Rajendra Devanda, Department of Dermatology and Sexually Transmitted Disease, National Institute of Medical Sciences and Research, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. rdevanda24@gmail.com

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Couppoussamy KI, Devanda R. Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata in a newborn: A case report and review of literature. J Skin Sex Transm Dis. doi: 10.25259/JSSTD_81_2024

Abstract

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) is a congenital disorder with the coexistence of pigmentary nevi and vascular malformation. The disorder can be localized to the skin or accompanied by systemic abnormalities. Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata is one of the subtypes of PPV characterized by Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenital (CMTC) and nevus cesius. Herein, we describe a case of phacomatosis cesiomarmorata with the nevus cesius and CMTC in a newborn with no systemic abnormalities.

Keywords

Cesiomarmorata

Newborn

Phacomatosis

INTRODUCTION

Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis (PPV) occurs due to a pathogenetic mechanism known as pseudodidymosis, which results in vascular malformation and pigmentary nevi in the newborn’s skin at birth. Recent reports of unusual associations between cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (CMTC) and nevus cesius in a small number of patients were labeled as phacomatosis cesiomarmorata.[1] CMTC is a persistent vascular malformation with a reticular pattern.[1] Herein, we describe a case of phacomatosis cesiomarmorata in a term neonate in the 1st week of life with a very uncommon combination of skin lesions, including lumbosacral nevus cesius, nevus cesius over the left shoulder, and CMTC with no associated systemic abnormalities.

CASE REPORT

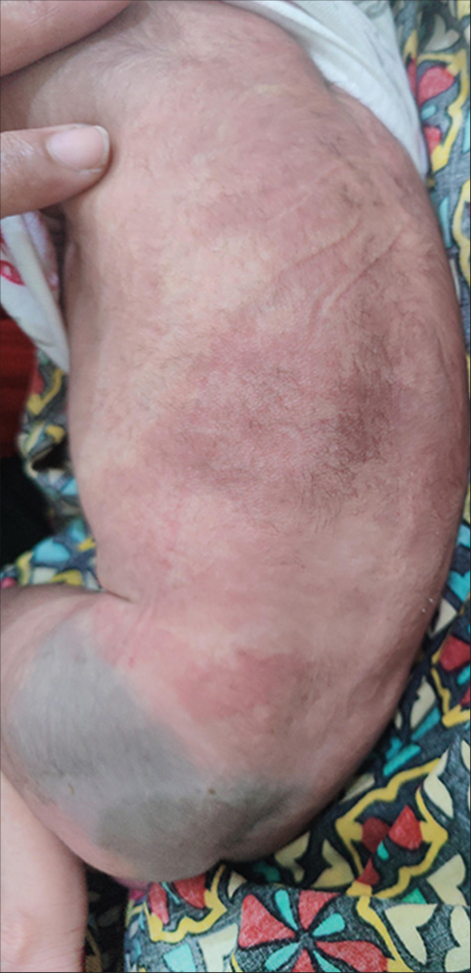

A term female neonate in the 1st week of life presented a history of reddish pigmentation over the trunk and bilateral lower extremities for 1 day. On examination, reticulate pink, red, blanchable telangiectatic patches were present over the face, trunk, and bilateral lower extremities, suggesting CMTC [Figures 1 and 2]. These erythematous patches were more apparent on the body’s left side. The lesions lacked an identifiable midline demarcation. An irregularly shaped, bluish-green pigmented patch with a wavy border was noted over the left buttock, with midline demarcation suggesting a nevus cesius. A similar irregular, bluish-green pigmented macule was noted over the left shoulder, suggesting a nevus ceisus [Figure 3]. There was no limb length disparity, soft tissue hypertrophy, or atrophy at the presentation time. Examination of the eyes done by a pediatric ophthalmologist was unremarkable. Nervous system evaluation performed by a neurologist was found to be normal. Mucosa, hair, nails, palms, and soles appeared normal. There was no significant prenatal history. The newborn’s birth weight was 2.9 kg (between 0 and −2 standard deviation). The parents had no history of consanguineous marriage. The parents or other family members had no history of hereditary diseases. There was no icterus, edema, or cyanosis of the extremities in the newborn. On the 3rd-month follow-up, erythematous patches and pigmentary nevi showed partial improvement [Figures 4 and 5]. Based on clinical presentation, the infant was diagnosed with phacomatosis cesiomarmorata and put on regular follow-up to detect any associated cardiac, ocular, and neurological anomalies.

- Ill-defined reticulate pink, red telangiectatic patches suggestive of cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita over the trunk and bilateral lower extremities.

- Ill-defined reticulate pink, red telangiectatic patches suggestive of cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita noted over the trunk with nevus cesius over the left buttock.

- Blue-green pigmentation with an ill-defined patch (nevus cesius) noted over the left shoulder region.

- Fading of cutis marmorata telangiectatica and nevus cesius were noted over the trunk.

- Fading of cutis marmorata telangiectatica noted over the trunk and left thigh.

DISCUSSION

A combination of vascular malformation and melanocytic nevi characterizes PPV. Conventionally, PPV was classified into four types by Hasegawa and Yasuhara.[2] Later, a PPV type V was added to the classification by Torrelo et al., in which there were CMTC and nevus cesius.[1] Happle classified PPV into three types, namely phacomatosis cesioflammea, phacomatosis spilorosea, and phacomatosis cesiomarmorata.[3] The recently updated classification of PPV is elaborated in Table 1.[4] The updated classification has six types of PPV, one among which is phacomatosis cesiomarmorata.

| Updated classification (types) | Capillary nevus | Pigmented nevus |

|---|---|---|

| Phacomatosis cesioflammea | Nevus flammeus | Nevus cesius |

| Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata | Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita | Nevus cesius |

| Phacomatosis spilorosea | Nevus roseus | Macular nevus spilus |

| Phacomatosis melanorosea | Nevus roseus | Hypermelanotic nevus |

| Phacomatosis cesioflammeomarmorata | Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita, Nevus flammeus | Nevus cesius |

| Phacomatosis melanocesioflammea | Nevus flammeus | Nevus cesius, hypermelanotic nevus |

PPV: Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis

The etiology of PPV is not fully elucidated, but the mechanism of pseudodidymosis is thought to be involved in its pathogenesis. Previously, PPV was thought to be due to twin spotting or didymosis. In twin spotting, an organism has heterozygous mutations on either of two homologous chromosomes. Somatic recombination produces genetically two different clones of neighboring cells that are separated by normal-appearing cells. However, this theory has been disproven. Recently, phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica was proved to be due to postzygotic mutation in Harvey rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog. Similarly, PPV was also thought to occur due to pseudodidymosis.[2,5] The most common syndromic associations of PPV are Sturge-Weber syndrome and Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Around 50% of the PPV patients can have associated systemic anomalies. Other associated conditions are renal agenesis, glaucoma, and central nervous system anomalies.[4] The neurological features seen in association with PPV are seizures, developmental delay, atrophy of the cortex, calcifications in the brain, hydrocephalus, and spina bifida. When there are no associated systemic conditions, PPV is typically a benign disorder and requires no treatment. Persistent skin lesions might improve with laser treatment. For pigmentary nevi, Q-switched lasers can be used and for vascular malformation, pulsed-dye laser can be tried.[6,7]

CMTC is a persistent localized or widespread vascular malformation characterized by a reticular vascular pattern. They show a checkerboard pattern with flag-like areas of reticulate vascular pattern showing sharp midline demarcation.[4,8] Our patient had lumbosacral nevus cesius, CMTC and nevus cesius over the shoulder with no systemic manifestations; hence, it was classified as phacomatosis cesiomarmorata. Nevus cesius, also called blue spots, are blue or gray-pigmented macules that commonly occur over the sacrococcygeal region. They are single or multiple and usually regress in childhood. On histology of nevus cesius, there are spindle-shaped melanocytes in the lower dermis.[2] The various associations reported by previous studies on phacomatosis cesiomarmorata are highlighted in Table 2.[1,8,9-22] Table 2 shows that the significant associations of phacomatosis cesiomarmorata are ocular, neurological, and cardiac anomalies. The common neurological anomalies associated with this are seizure and global developmental delay. The other reported associations of phacomatosis cesiomarmorata are glaucoma, limb atrophy or hypertrophy, and atrial septal defect.

| Study | CNS associations | Cardiac associations | Ocular associations | Other associations | Genetic mutation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thomas et al.[10] | Mild developmental delay Periventricular leukomalacia | Nil | Nil | Nil | GNA 11 mosaic mutation |

| Sliepka et al.[11] | Cerebral atrophy, corpus callosum hypoplasia Hypomyelination, Bilateral optic nerve Hypoplasia, and left lateral ventricle enlargement Recurrent seizures, Global developmental delay and generalized hypotonia |

Questionable mass on the right ventricular wall. | Bilateral congenital glaucoma | Two-sided right renal arteries Left renal artery stenosis Interpolar cortical cysts, Small left lower renal pole, Right lung apex and left lung base atelectasis. Gastroesophageal reflux disorder. |

GNA 11 mosaic mutation |

| Kumar et al.[12] | Mild global developmental delay Right frontal and left temporal developmental venous anomaly |

Nil | Nil | Nil | GNA 11 mosaic mutation |

| Kaur et al.[13] | Nil | Nil | Melanosis oculi | Hypospadias, | - |

| Cifuente et al.[14] | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil | - |

| Nanda et al.[15] | Mild developmental delay. Prominent sylvian fissure and reduced deep white matter Absent A1 segment of anterior cerebral artery and posterior communicating artery. Prominent cortical sulci with pseudo schizencephaly |

Mild atrial septal defect Absent inferior vena cava with hemiazygos continuation to innominate veins. |

Bilateral glaucoma | Limb asymmetry | - |

| Torrelo et al.[16] | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil | - |

| Du et al.[8] | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil | - |

| Fernández-Guarino et al.[17] | Nil | Nil | Melanosis oculi | Nil | - |

| Jun et al.[18] | Old lacunar infarct in right centrum semiovale | Nil | Nil | Hypertrophy of right side of the face and leg. | - |

| Larralde et al.[19] | Mild asymmetry of the lateral ventricles | Nil | Unilateral corneal opacity. | Nil | - |

| Dutta et al.[20] | Seizure, intracranial vascular anomalies | Nil | Nil | Nil | - |

| Torrelo et al.[1] | Slight asymmetry of the hemispheres Asymmetry of ventricles, decrease of left periventricular white matter. |

Nil | Blue sclera, reduced size of cornea Nevus of Ota |

Geographic tongue, hypertrophy of left buttock and thigh | - |

| Smith et al.[21] | Nil | Nil | Glaucoma | Nil | - |

| Byrom et al.[22] | Nil | Nil | Nil | Limb asymmetry | - |

CNS: Central nervous system, GNA 11: Guanine nucleotide binding protein alpha 11

For early diagnosis of cardiac, ocular, neurologic, and renal manifestations, it is crucial to carefully assess a baby who has PPV. They should be put on regular follow-ups to look for systemic associations that can also become evident over time. Systemic abnormalities were absent in our patient at presentation, and the newborn was advised to have regular follow-ups. There are no proper recommendations available for the frequency of follow-up. Reports of patients with phacomatosis cesiomarmorata with associated neurological involvement showed genetic mutation in guanine nucleotide binding protein alpha-11.[9,10] However, these reports did not highlight the management and outcome. Genetic testing could have helped to see for the associated mutation, but it could not be done for our patient due to cost constraints. Further studies on phacomatosis cesiomarmorata are needed to frame guidelines on the follow-up and management of this condition.

CONCLUSION

We describe a case of phacomatosis cesiomarmorata with nevus cesius and CMTC in a newborn with no systemic features. Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata is characterized by the occurrence of nevus cesius and cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita. They can be associated with multiple systemic abnormalities. After diagnosis, screening for the ocular, cardiac, nervous system and renal anomalies regularly is essential to detect complications and management.

Acknowledgments

Nil.

Ethical approval

Institutional Review Board approval is not required.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for manuscript preparation

The authors confirm that there was no use of artificial intelligence (AI)-assisted technology for assisting in the writing or editing of the manuscript and no images were manipulated using AI.

Financial support and sponsorship: Nil.

References

- Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and extensive mongolian spots: Type 5 phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:342-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis type IVa. Arch Dermatol. 1985;121:651-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis revisited and reclassified. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:385-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phacomatosis spilorosea versus phacomatosis melanorosea: a critical reappraisal of the worldwide literature with updated classification of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. Acta Dermatovenerol Alp Pannonica Adriat. 2021;30:27-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phacomatosis pigmentokeratotica is a “pseudodidymosis”. J Invest Dermatol. 2013;133:1923-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treatment of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis: A combined multiple laser approach. Dermatol Surg. 2003;29:642-6.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laser therapy treatment of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis type II: Two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2013;7:55.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita and aberrant Mongolian spots: Type V phacomatosis pigmentovascularis or phacomatosis cesiomarmorata. JAAD Case Reports. 2016;2:28-30.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita being caused by postzygotic GNA11 mutations. Eur J Med Genet. 2022;65:104472.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosaic activating mutations in GNA11 and GNAQ are associated with phakomatosis pigmentovascularis and extensive dermal melanocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 2016;136:770-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GNA11 brain somatic pathogenic variant in an individual with phacomatosis pigmentovascularis. Neurol Genet. 2019;5:e366.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Extracutaneous manifestations in phacomatosis cesioflammea and cesiomarmorata: Case series and literature review. Am J Med Genet A. 2019;179:966-77.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata with hypospadias and phacomatosis cesioflammea with Sturge-Weber syndrome, KlippelTrenaunay syndrome and aplasia of veins--case reports with rare associations. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21 Available from:

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Phacomatosis cesiomarmorata in an 8-month-old infant. Int J Dermatol. 2009;48:1110-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis: Report of four new cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:298-303.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Large aberrant Mongolian spots coexisting with cutis marmorata telangiectatica congenita (phacomatosis pigmentovascularis type V or phacomatosis cesiomarmorata) J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2006;20:308-10.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis: Clinical findings in 15 patients and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:88-93.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis type Vb in a three-year old boy. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27:353-4.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phacomatosis pigmentovascularis type Va in a 3-month old. Pediatr Dermatol. 2008;25:198-200.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis: A clinical profile of 11 Indian patients. Indian J Dermatol. 2019;64:217-23. Erratum in: Indian J Dermatol 2019;64:420

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- JAAD grand rounds quiz. Red, purple, and brown skin lesions in a 2-month-old boy. Phakomatosis pigmentovascularis type V. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012;66:341-2.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Red-white and blue baby: A case of phacomatosis pigmentovascularis type V. Dermatol Online J. 2015;21 Available from:

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]